Bucksport Maine Finds Its Heart & Soul

This article first appeared on the Our Towns Civic Foundation website on August 18, 2021, which you can see here.

If you’re in Maine, heading Downeast from Portland on coastal Route 1, you’ll cross the stunning Penobscot Narrows Bridge, and then the smaller East Channel Bridge. At the end of that second bridge, you’ll face a decision. Turn right, as most people do, toward Mount Desert Island and the Acadia National Park. Or turn left, as most people don’t, for a look at Bucksport, population 5000. If you turn right, you’re missing something. One plucky Bucksport resident told us on our recent visit there that they considered posting a sign at the end of the bridge, Don’t Turn Left, to see what might happen.

Why turn left? Because we think that Bucksport, which has faced about as big an economic downfall as one can face, has lessons for us all on how to renew a town.

Bucksport fronts onto the Penobscot River, part of Maine’s spectacular coastal scenery. Bucksport’s paper mill, originally known as the Maine Seaboard Paper Co., opened 90 years ago, and was renowned as a producer of high quality slick paper, used by the likes of Time magazine and of course Maine’s L.L. Bean catalog. The mill ping-ponged through 6 different owners, employed more than 1300 people at its peak, and was paying 40% of the town’s taxes when it closed down suddenly in December, 2014, eliminating jobs for nearly 600 people, about half of them Bucksport residents.

The closing was, of course, an immediate shock to the people of Bucksport, like the death of a beloved grandparent, whom you see aging, but irrationally imagine will be with you forever. Unlike in many other towns where mills, factories, or mines have closed and people clung to hopes for revival, several people told us that Bucksport residents knew immediately that the mill era was over. The doors had slammed shut and they weren’t going to open again. Ever.

Mill-town way of life was all that most residents of Bucksport had ever known. (Although several people told us that Bucksport had liked to think of itself as “a town with a mill,” rather than as a mill town.) After the closure, many straddled two outlooks, one of shock and grief and the other of determination and resolve to control their destiny where they could.

Sue Lessard, who arrived as town manager in 2015 and whom we spoke with in Bucksport this summer, relived the history as of that point. “There were two ways to go. Should we make ourselves small to accommodate this loss of this major industry and all this taxation value to the community? Or should we do something else? And Bucksport decided to do something else.”

Each town’s version of this genre of seismic change is unique; Bucksport’s version was more auspicious than most. The town had two strong assets in their favor: a financial cushion from decades of far-sighted economic planning, and a tradition of infrastructure improvements.

Roger Raymond, who had been Bucksport’s town manager for 27 years, had been squirreling away a portion of the town’s revenues, during the fat years when the mill was running full-tilt and paying its large share of local taxes. By the time Raymond retired in 2012, this rainy-day fund had reached a handsome 8 million dollars. During those years, the town had begun investing in infrastructure, including hiking trails, a waterfront walk, a growing business park, schools, public places and spaces. Residents came to appreciate the abundance of amenities that improved their quality of life. So at that moment in 2014 when the mill closed, the town had a solid starting point.

During our 100,000 miles of travels around the country since 2013, my husband, Jim, and I have seen many towns face transitions like Bucksport’s. A major economic failure is followed by the call for a soul-searching look into the abandoned mine, or at the quieted factory floor. We have heard and seen towns shrink into their own shadows, or (rarely) luck into an economic-backed renaissance coming out of nowhere. We have heard people say: “We’re waiting for someone to come and save us,” and , with a very different emphasis, “We know no one is coming to save us.” Most often, we have heard people ask the practical questions: how do we recover, how do we move ahead, what are we supposed to do?

Bucksport, for its answer, turned to a program we had first heard about nearly six years ago, the Orton Family Foundation’s Community Heart & Soul program. We had been trying to see first-hand a town that had engaged in Heart & Soul (H&S), and finally, after the long covid lockdown, we made it to Bucksport.

We wanted to learn about Community Heart & Soul’s® (H&S) step-by-step, citizen-led process. Its aspiration is strongly democratic — to reach community consensus on shared values. Its goal is strongly practical — to put in motion an action plan to support those values. A trained H&S coach shepherds a town through the process. Jane Lafleur, Bucksport’s coach, told us that the coach’s role was to counsel and respond, but emphasized that it was not to lead.

Bucksport, we had heard, had become somewhat of a poster child among the more than 100 H&S towns nationwide. Plus, for us, another lure was that the town is nestled into one of America’s natural treasures, the coastline of Maine.

Like the rest of America, my husband, Jim, and I were house-weary and agitated from Covid lockdowns and eager to get away. Our small Cirrus propeller plane, the workhorse for our more than 100,000 mile journey over the past eight years, was out of its annual inspection and ready to fly. I have to say at this point: while we have always appreciated that the privilege of flying this little plane makes the journey as rewarding as the destination, this time we felt immeasurably more grateful and excited.

The flight from our hometown of D.C. to mid-coast Maine is about 3 hours over sites familiar to us: the suburbs and farms of the mid-Atlantic, the slice of the mighty Susquehanna River, the smattering of quarries and often nearby prisons, the low-altitude view over West Point’s parade grounds above the Hudson River, the diagonal cut through Connecticut and Massachusetts, and the pièce de résistance, the stunning shoreline of the Maine coast. On the blue-sky day that we flew, Maine was showing off, with thousands of small boats, strings of beaches, cluster after cluster of small islands, little towns with church spires, and its rugged, rocky inlets and bays.

Community Heart & Soul is one of several town renewal models that we have learned about (more on others soon). It started with the vision of founder Lyman Orton, who describes himself as the proprietor of his longtime family-owned Vermont Country Store, which has long charmed New England and through catalogs, America, with what they describe as its “practical and hard-to-find” products. Orton’s premise with his foundation is that residents of a town know its “heart and soul” best and can turn that knowledge into the power to change, gain confidence, and even muster economic development.

Here’s how the H&S 4-step model works:

- Engage the community players, lay the groundwork, and communicate. For the first few months, townspeople come together as partners and volunteers to build their networks, figure out how to proceed, and open communication channels.

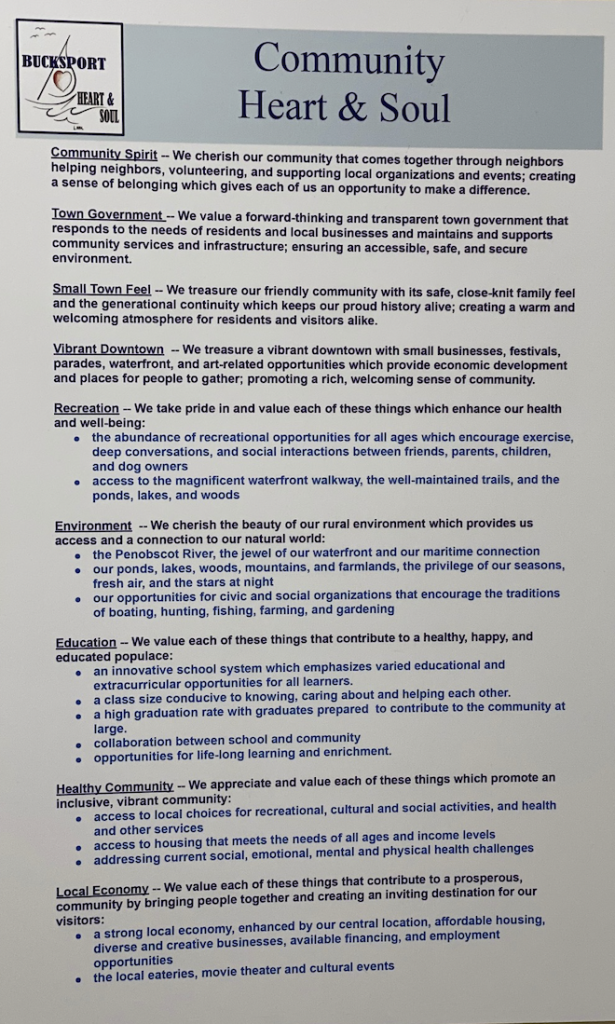

- Collect residents’ stories about what matters to them in their hometown and about specific ideas for action. Storytelling is a hallmark of the process. Through hundreds of stories, the values of the town emerge, and the people of the town identify and articulate a set of qualities (called statements in H&S vocabulary) that they want to define their town. A framed list of the statements hangs in the lobby of Bucksport’s town hall, a reminder for the citizens of Bucksport and a point of reference for elected leaders and officials to guide their decisions.

Nancy Minott, an early coordinator for the H&S project and now a trustee for the Buck Memorial Library, recalled for us the reach of citizen engagement from an early town meeting in Bucksport:

“I remember, this man stood there, and he just looked at everybody. And he said, ‘I have never, never had the courage to talk. You know, I was never invited to share a story. And this is the first time, so I might be a little nervous.’”

“To me,” says Minott, “that was just exactly what you learned: people that hadn’t had a voice were finding a voice.” - Make a Plan. This is the slow-cooking meat and potatoes portion of the process, to prioritize action items that will serve the town values, and to solicit people and partner organizations to execute. For example, in Bucksport, one statement is Recreation. Citizens suggested relevant action items, such as expand the Trails System, and install exercise stations, and nature walks, and benches and bike racks. Form a walking club, an outing club, provide picnic areas. Build a (multi-generational) playground and a bocce court, a skateboard park, a bowling alley. Expand the marina.

- Act. Start in on the task list with responsible, accountable volunteers and community organization partnerships, bearing in mind that the this is the beginning of a long-game.

Along the way, Bucksport assembled 100 volunteers, leaders, partnerships, from students to radio announcers and civic organizations like the YMCA. They worked for 10,000 hours. They collected 250 stories, listened for 400 hours. They identified 9 strong statements of their values, and identified 82 tasks, a huge number compared with the usual 10 or 15 action items other H&S towns have undertaken.

Bucksport volunteers recounted the hard work behind the numbers of people hours and projects. Hard work, hard work, hard work, we heard time and again. A resident from nearby Gardiner, Maine, which was near completion of the H&S work, came to talk with Bucksport when they were just beginning.

Chris Johnson, a founder of Bucksport’s H&S project, described a moment of that meeting to us, “Somebody asked if the process was hard. He goes, “Oh God, it’s the hardest thing you’ll ever do.” And he was right. Only, he underplayed it, because it’s so much work. And yet, there’s a permanence to it, I think. And for the town of Bucksport, we could have done better, but the seeds have been planted. And the seeds have been sown.”

A crucial part of the H&S philosophy is that towns don’t just wrap up their renewal process after two years and store their statements somewhere on a dusty shelf. Rather, ideally, towns continue to practice what they have put into place through listening, working and acting cooperatively. H&S may not be for every town. But it is one answer to the question we hear so often from residents who want to improve their towns: what are we supposed to do? The Heart & Soul process offers specific actions, step-by-step.

In one obvious way, Bucksport is a special case. Could it have accomplished its efforts without its 8 million dollar war chest and its foundation of infrastructure already begun? It’s impossible to know. “If they hadn’t put away as much money, it would have been harder,” Sue Lessard told us. But like many others, she says that it was a help but not the determining factor. “To be perfectly honest, I don’t know that the people’s attitudes would have been different, but it would have been a steeper climb.”

Shortly after the official Heart & Soul process was complete and addressing the specific tasks had begun, Covid hit, interrupting everything. When we visited with Nancy Minott, we asked her “Now what”? Minott told us that the residents had picked up the string again to execute their Heart & Soul action plan. “This spring, when things started to get a little bit quieter, we started to say, ‘Yeah, we need to get back to our Action Plan and look over our action ideas from the citizens.’ I think it’s really important that these ideas do materialize, because that’s respectful. I mean, why bother to put your ideas out there, if you’re not going to do that.”

So, next time you’re on Route 1, think about turning left after the bridge, even if you see a sign that says “Don’t Turn Left.” Take a walk along the river, look for the granite bench that says “Class of 2020 Inspiration During Isolation”, stop for a craft beer (made by real friars) at the Friar’s Brewhouse, visit the history museum, swing by the town pool to find all the kids, try a glass of wine at Verona Wine and Design, and when you look up at the hulk of the paper mill, think of it not as a loss but as an opportunity that propelled the citizens of Bucksport to recreate a vibrant town.

James and Deborah Fallows, authors of Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America, spent five years crisscrossing the country in their single-engine plane, visiting dozens of small cities and towns. Wherever they touched down, they would interview local residents, town officials, business owners, librarians, and others to learn how communities were reinventing themselves in the face of changing economic and social conditions.

Our Towns became a national best seller and was recently made into a feature-length HBO documentary film. The Fallowses also launched Our Towns Civic Foundation, a nonprofit organization that serves as a platform for sharing stories of small-town innovation and resiliency. Through the foundation, they connect and support individuals across America who are working to improve local communities.

The Fallowses also launched Our Towns Civic Foundation, a nonprofit organization that serves as a platform for sharing stories of small-town innovation and resiliency. Through the foundation, they connect and support individuals across America who are working to improve local communities.

Join Bucksport and other towns across the country looking to build stronger and more vibrant communities. Apply today for $10,000 to bring Community Heart & Soul to your town.

Grant funding requires a $10,000 cash match from the participating municipality or a partnering organization.