How Local Governments Can Engage Residents Of All Ages

This article first appeared on the Our Towns Civic Foundation website on December 14, 2022, which you can see here.

When community members can’t, or don’t, or won’t, go to town halls to attend local government meetings, some local elected officials have found a way to go to their constituents.

Reporting from towns across the country, I’ve heard from multiple people that not all residents can make a morning meeting in council chambers, an afternoon gathering in a library, or an evening assembly in a community center. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ 2020 Our Common Purpose report puts numbers to what I’d been hearing: just 11% of Americans attended at least one public meeting on a local issue last year.

In a time of perceived division and discontent at the national level, I became more curious to explore how today’s town leadership can bring more of their communities into local government through new approaches to engaging their community members.

Earlier this year, I met Isaac Tucker, a Borough Council Member in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania. I wrote about Isaac, and his wife, Heidi, first here, and then followed up again here. In the second piece, Isaac told me more about the challenges he experienced firsthand: His local government, which he sought office for and was elected to in 2017, was working to serve its constituents, but Isaac believed it could reach more of the town’s people and needs. So, he turned to Community Heart & Soul® in 2019.

Tucker is part of a growing list of municipal officials and town managers who have been a part of introducing Community Heart & Soul (CH&S) to their towns. A resident-driven, community-development process, CH&S can help town leaders better serve their constituents through its inclusive approach (CH&S is a supporter of and partner with Our Towns). The process, which typically lasts around two years, asks residents what they love about their towns and what they wish their town could improve. Their responses become data that can be used by town leadership and public officials to make informed decisions on how to govern for the betterment of their towns going forward.

Some 600 miles to the north, Susan Lessard, who became town manager in Bucksport, Maine, in 2015, had a similar experience. Lessard leveraged the CH&S process a year after taking office to help the town figure out where to prioritize scarce resources after a mill closure left 40% of Bucksport’s workforce without jobs. As Our Towns has written about in detail, CH&S helped Bucksport develop an action plan and guide its leadership towards taking steps to revitalize the community.

Autumn Vogel, a city council member in Meadville, Pennsylvania, used the values that CH&S produced as a platform for her campaign for local office in 2019. She became passionate about the CH&S process as its project coordinator in 2017 while she served as Meadville’s community development coordinator within the city’s redevelopment authority. She now uses the output of Meadville’s CH&S process, which had an emphasis on creating affordable housing, to focus her efforts as a public official.

Lessard, Tucker, and Vogel all told me that to effectively represent the communities they serve, they needed an inclusive approach, a way to both meet people where they are, and ensure they know their voice is welcome.

At the outset of the CH&S effort in Bucksport, Lessard personally invited all the town officials and everyone running for office to an informational meeting with the public to learn about CH&S. Community members from different backgrounds were offered a chance to give their perspective. Lessard told me that intentionally bringing in a broad array of voices was critical to getting buy-in from the community.

“For us, Heart & Soul was about grassroots engagement of residents,” Lessard told me. “That had a huge appeal to me because that was the information we needed as Bucksport entered a very critical juncture in our history: what people in the community felt was important, what they cared about, and what they wanted to have as a part of their future.” Bucksport, which Lessard has described as a conservative, family values-oriented community, developed community values statements that are now posted in their town office.

Jim Burgess, a former local principal who is now one of the leaders of the CH&S process in Dillsburg, echoed that sentiment. “The key is not to come in with your own ideas, but instead to shut up and listen to other members of the community,” Burgess told me.

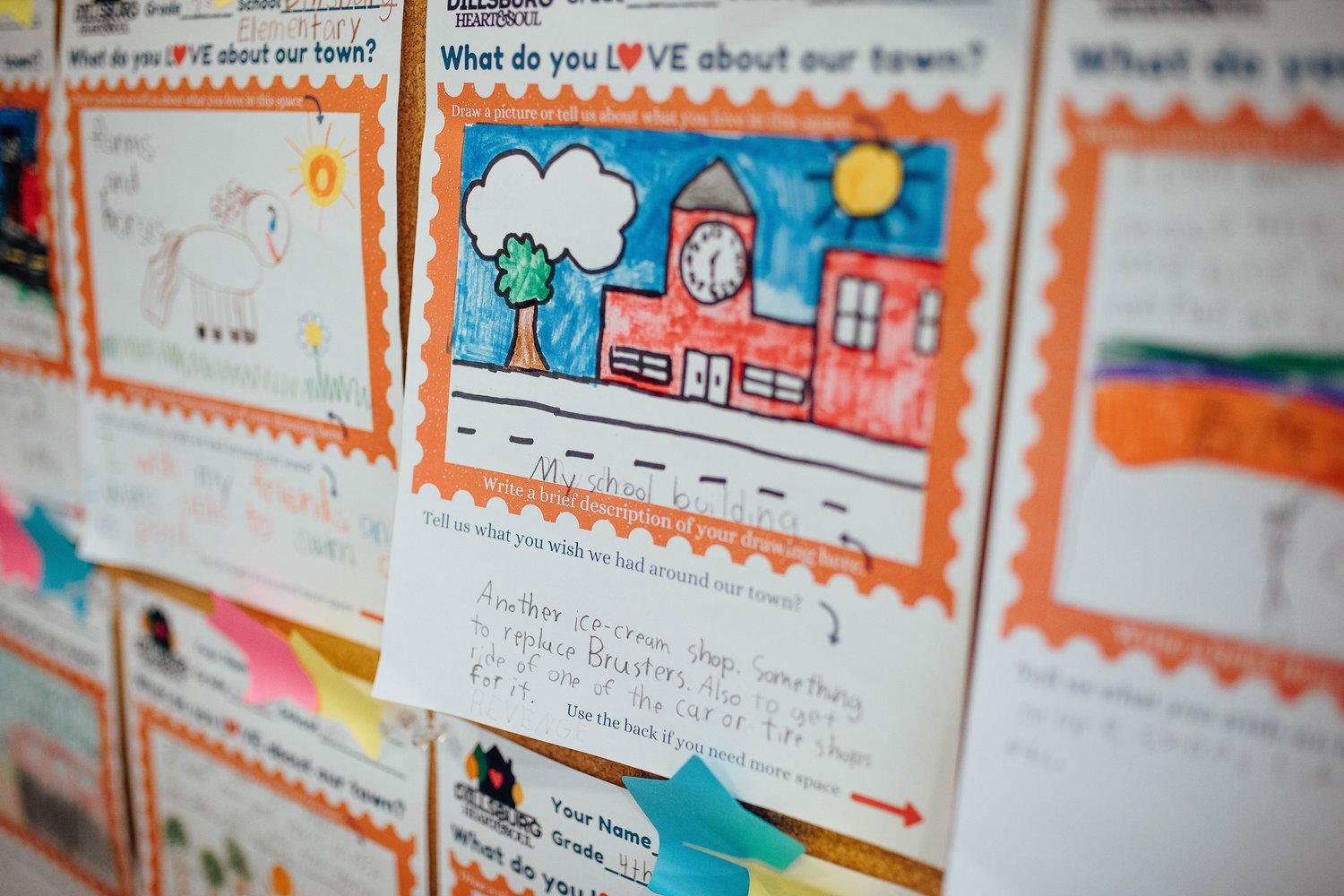

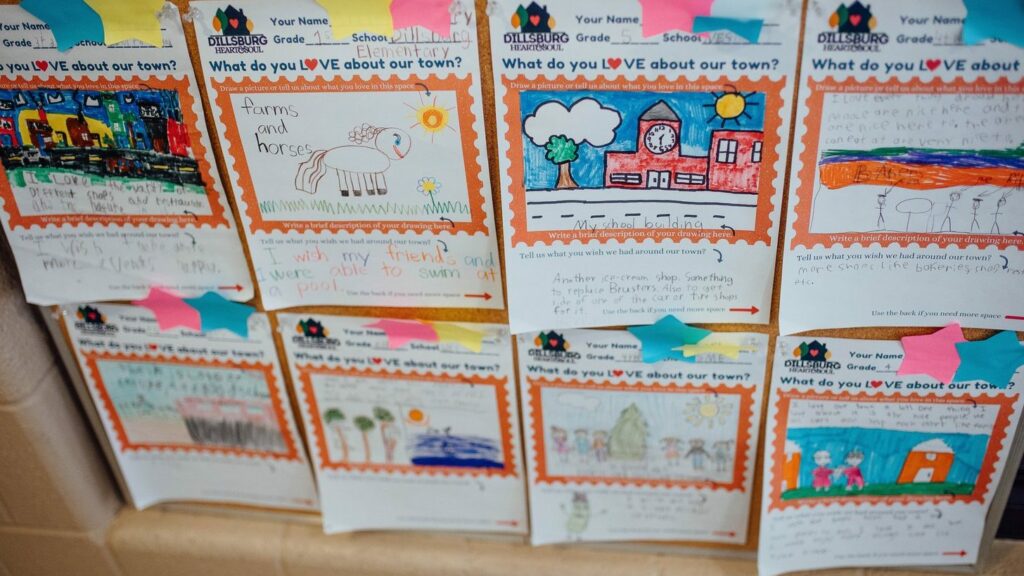

He mentioned that CH&S speaks to community members where they normally gather, beyond traditional channels for civic engagement: places like parks, social clubs and gatherings, libraries. Tucker explained that the process can even extend to the town’s youngest residents by reaching out to kids in schools.

“We set up a worksheet for kids to draw how they’d like to see the town change. They drew roller coasters, beaches, and pools. The idea is to get our kids invested in the town’s future. They’re the ones who are going to live in this town over the next 60 years, they should feel like they have a stake in shaping it,” Tucker told me.

There are a couple of important add-on benefits of the CH&S process. First, as we’ve written about in Dillsburg, people who feel heard gain agency and are willing to commit more time and energy to their towns. The Tuckers’ Downtown Dillsburg Initiative helped spur new collaborations, businesses, and community engagement.

Second, the data collected through CH&S surveys and interviews becomes a public good. Tucker explained that the Dillsburg team has collected over 2,000 data points by asking Dillsburg residents what they value about their town and what they’d like to see improved. Their answers form a comprehensive wish list for the community.

“CH&S data becomes a repository that can be handed to any church, nonprofit, or organization seeking to raise money for a cause,” Tucker told me. “Heart & Soul data makes it much easier to write grant proposals to demonstrate a community identified need.” We reported on similar outcomes in Kershaw, South Carolina, where the CH&S process and data informed a grant application to convert a vacant bank building into an early childhood center.

Creating a platform to give community members an opportunity to be heard can build much-needed trust in a time when division receives outsize attention, as I saw in Dillsburg, and we have seen playing out in Bucksport, and Meadville, and Kershaw, and other towns. CH&S isn’t a silver-bullet solution, nor is it intended to be, but it does offer community advocates seeking to make things better – or to keep things that are working the same – a foundation on which to rest and build their case. That’s a solution worth trying in any town.