Fountains of Youth for Towns

This article first appeared on the Our Towns Civic Foundation website on March 15, 2022, which you can see here.

The life and spirit of any town or city depend on its ability to attract and retain people. In a time when many worry about brain drain, how communities keep their young people, or bring them back, or attract newcomers illustrates a place’s sense of and attention to renewal.

When we first met Jake Soberal in Fresno, California, in 2015, he was in his late 20s. He had gone East for college, worked as a lawyer for a few years, and was newly returned to Fresno to become part of the entrepreneurial renewal of the town.

Jake might have been as surprised as anyone else to find himself back in Fresno. As Jim Fallows wrote back then, Jake had recalled the commencement address he delivered at his high school in Clovis, the city bordering Fresno: “I can distinctly remember sitting up there, this arrogant 18-year-old thinking, you know, these folks really ought to enjoy this speech because they’ll never see me here again.”

Well, they did see him again. He returned to co-found Bitwise Industries, a multi-missioned technology company embedded in the economic, cultural, and social life of Fresno, and committed to arming a new upskilled workforce to help Fresno realize its aspirations. We were impressed enough by their work and spirit of Bitwise, that we chose them to build the very website you are reading now.

The comment from Soberal’s 18-year-old version of himself (coming in part from being 18 years old, of course) speaks to a concern we hear time and again in communities all over the country. The adults are worrying—deeply—that if their young people don’t engage, see opportunity, want to stay, or even entertain the idea to return, then their towns are in trouble. Any town’s vitality and even survival depends on ongoing decisions about whether people want to live there. Attracting young people as they are starting careers and family is an enormous step toward a vibrant future for the community.

Jason Neises, who got a degree in history and politics from Northern Iowa University in the early 1990s and then served in the Peace Corps in Africa, has been working in small towns in eastern Iowa for over six years in community development for the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque. There he uses planning processes, like the Community Heart & Soul (CH&S) approach that we have previously described in Bucksport, Maine, and Galesburg, Illinois. CH&S is based in Vermont and is a partner with Our Towns in reporting on small-town development.

Neises believes that engaging the young people and giving them reason to return is neither a pipe dream nor a lost cause. There is reason to believe he’s right: Ben Winchester of the University of Minnesota Extension has been charting a shift from what he calls “brain drain” of those in their late teens and 20s to “brain gain”, as those in their 30s and 40s return to rural hometowns, with families in tow and grown-up commitments in hand. Covid has given this kind of migration a boost, with young people moving back or to more rural roots for lifestyle and family reasons. Stephanie Sowl from Iowa State University reports that early and positive feelings about their hometowns is indeed a noteworthy reason for high-achieving young people deciding to return home later.

How to transition from the youth exodus worry to action? Or as many town citizens have put it to me: What do we do? How do we start? Here are some answers we have heard:

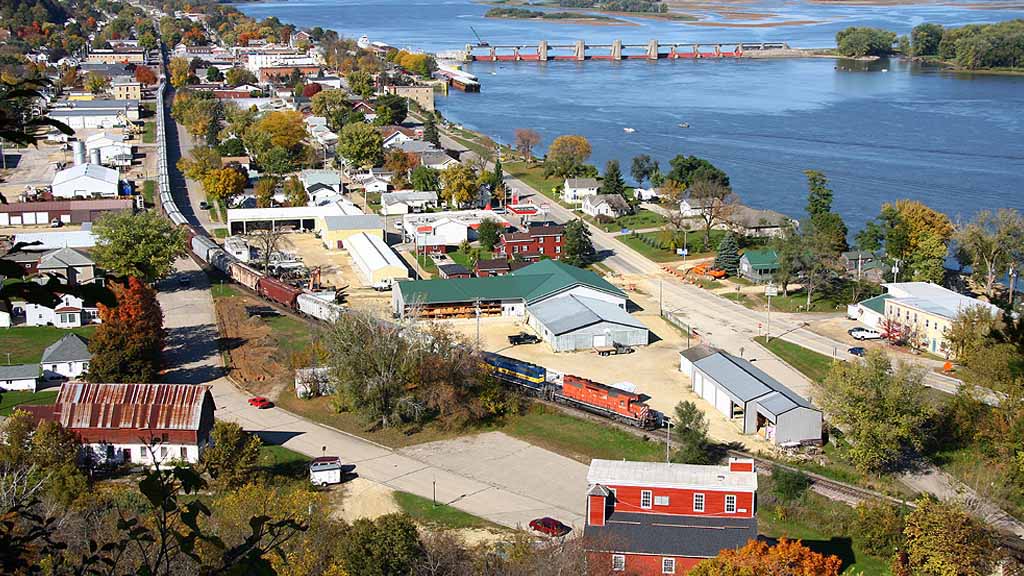

Open the doors and invite them in. — Bellevue, Iowa, population 2,200, is one of Jason Neises’s towns. A 2017 survey by CH&S and the Center for Rural Strategies found that only 15% of young people said they had been asked for their input about their town’s future, but 68% said they would volunteer if asked.

The public school system—a potentially readymade asset in any town—played a fundamental role in bringing the young people of Bellevue into the town’s development efforts, to include those whom Jason Neises calls the “missing voices in the community.”

They made room in the curriculum and the students’ days for them to take part in city-oriented projects, like planning for bike lanes and town parks, and to participate on the city council. Bellevue also opened a project-based education center, called BIG, for students to move beyond school to learn and “broaden their horizons into the Bellevue community.” Right now, during this late winter week, the BIG website is advertising for community orders for the products from their aquaponics project—kale, watercress, lettuce, and mushrooms. And they are featuring the progress of three high school juniors who are renovating the basement of BIG, a former button factory in downtown Bellevue, with a soundproof recording room. They are now working on insulation, drywall, and ceilings. Collaborations among a town’s organizations and schools are not always as optimal as they are in a town like Bellevue. It takes the right town leadership to make it look easy.

Some towns and organizations push hard to find and bring in young people from other venues, like youth groups, churches, scouts, 4H, Boys and Girls clubs, and FFA. Laura Furr from the National League of Cities points out that when tackling the hardest issues, like homelessness and social justice, it’s important to find the authentic young voices who can speak from experience and personal perspectives. Where are they? Look to the juvenile justice groups, foster care, child welfare agencies, and homeless organizations to find them.

Listen to them. — Judy Larson is a community activist in the small town of Lemmon, South Dakota, population 1,200. Over the past two years of pandemic lockdown, I have talked with her frequently, as I described in this earlier post.

Larson told me about generational and cultural gaps between the adults and the young people, even when they sit at the same table. While (well-meaning) adults may say, “Oh, we have a youth member on our board,” or “Let’s ask the kids in the Honor Society to do that,” the young people hear those intentions differently. Larson relayed what her husband, a former math teacher, reminded her: Kids can suss out pretty quickly when it’s not a real situation, when the adults in the room are not listening to them.

Ali Lightfoot is now general manager for KVMR radio in Nevada City, California. Several years ago, living in Paonia (pay-oh-knee-ya) Colorado, where she was production manager for KVNF radio, she had an idea for a radio program, called “Pass the Mic”. The show would be produced and delivered entirely by young people. The town would be – literally and figuratively – listening to the young people. Lightfoot described what she heard when the young reporters interviewed coal miners and others about the history, economics, and experiences of working in the Hinsdale County mines.

They approached their interviews differently from adults, she told me. As kids, they would start at a more basic level of understanding the topic, (and could get away with that), with no political agenda (not yet acquiring the baggage that adults often carry), unveil their interviewees (with disarming bearing). They would, for example, ask rough-around-the-edges coal miners, ‘Tell me how mining actually works.’ ‘Why do you do this?’ ‘What do you love about your job?’ This approach elicited heartfelt conversation rarely heard among adults, Lightfoot reports, and says about the youth, “We don’t ask them what they think very often. We should learn from them.”

Give them pizza. Teach them skills. Go for the Easy wins. — The group HEAL Winchendon, in the Massachusetts town of 10,000 people, describes itself as “more than a project… a community movement for long lasting change to improve the health and quality of life for Winchendon’s residents.” Among their many institutional partners is a Youth Changemaker group of local high schoolers, whose work became streamlined into the system through a progressive 2018 Massachusetts law, requiring public high schools provide a student-led, non-partisan civics project for each student.

Miranda Jennings, who works with HEAL, which is also a new partner with CH&S, described two student initiatives in their town. Their students were very concerned about sexual orientation discrimination, which they saw as a problem. Their idea was to raise awareness through a kickball game. Jennings listened, agreed on the kickball, and suggested they might think even bigger. Had they heard about city proclamations? They hadn’t. “Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know,” she said. So, the students wrote a proclamation to recognize Pride Month in June 2021, and presented it to the city council. It was approved. “It was actually a very easy win,” Jennings said. The adults in the community were astonished, saying, “The kids did that?”

The second was more complex. The students wanted the young people to feel “proud to live in Winchendon, proud to be a resident here,” a sentiment that they felt was lacking. What they also saw lacking was a teen space in their town. They thought a teen space could be the vehicle for young people feeling more happy—and proud—about their town. Their first step was securing a modest mobile pushcart, which they hauled to monthly summer events in the park in 2021, to raise awareness and money toward their ultimate goal, a brick and mortar teen café. Shrewdly, and intentionally, they lobbied to place a student on the town board that was creating a physical makerspace, to be sure there would room for the café inside that makerspace.

This video shows the planning, preparation and newly-honed speaking skills that the students used to present their case to the United Way. They were rewarded with a $500 check for their teen café.

Adult supervision and proceed with passion. — The adults I spoke with had their own set of takeaways from working with the young people. While the youth identified gaining what you’d expect, crucial, real-life skills and a new understanding of their hometowns, the adults offered these.

From Massachusetts to Iowa to California, adults described learning to check their initial reactions to a crazy-sounding idea, take a step back, and move from “I don’t know if you can do that” to “OK, what is our first step.”

Radio producer Ali Lightfoot said that matching her own passion for radio work to the youth radio project was critical to their successes. And now she sees the value and necessity of passing this legacy down to someone equally as passionate, lest it disappear, as it did when she moved away from Paonia. In Nevada City, Lightfoot has introduced a brand new program for and by young people, called the Youth News Corps.

Jason Neises points to longevity and sustainability. What happens when, inevitably, powerful individuals in crucial organizations come and go—managers of chambers of commerce, mayors or city managers, directors of local community colleges, and the young people themselves. (Teachers, he says, tend to stay around longer.) Who will be there to make sure that the systems enabling youth engagement stay in place, and that lessons will be passed along. Neises says that his veteran status as multiple-times coach for several local communities in the CH&S process and his longtime work in the community foundation helps. He can spot programs becoming stagnant or going untended. He can assume license to approach newcomers and suggest “Let’s have lunch sometime,” as a way to renew or revive energy.

I keep returning to a mantra Jim and I heard in Winters, California (population 10,000) during our reporting trips there. We met young adults in town who were starting businesses and raising young families. Half of each couple was born and raised in Winters, and had returned. The other half were spouses from away, but who had words to pass along. “Be forewarned,” they said, “that if you marry someone from Winters, you will end up living in Winters.”

I have tried to figure out what magic Winters creates (besides being a really pretty small town, in a beautiful part of the country, with a rich agricultural heritage and very nice people) to embed this affection in the DNA of the young people who grow up there. I don’t know the answer. But I think I can see that some of the approaches in Winchendon, or Bellevue, or Fresno today may be part of the answer. Or it may just be how one of the kids from the pushcart project in Winchendon described what he experienced, when he said, “The adults are always on the ball.”

Deborah Fallows is a writer and a linguist. She has written for The Atlantic, National Geographic, Slate, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Washington Monthly. She is the author of three books including Our Towns: A 100,000 Mile Journey into the Heart of America (2018), a New York Times bestseller co-written with her husband, James Fallows. The HBO documentary, also called Our Towns, based on the book, is now streaming on HBO Max. Deborah and James founded the nonprofit Our Towns Civic Foundation to promote the ideas of resilience and renewal in towns across America.